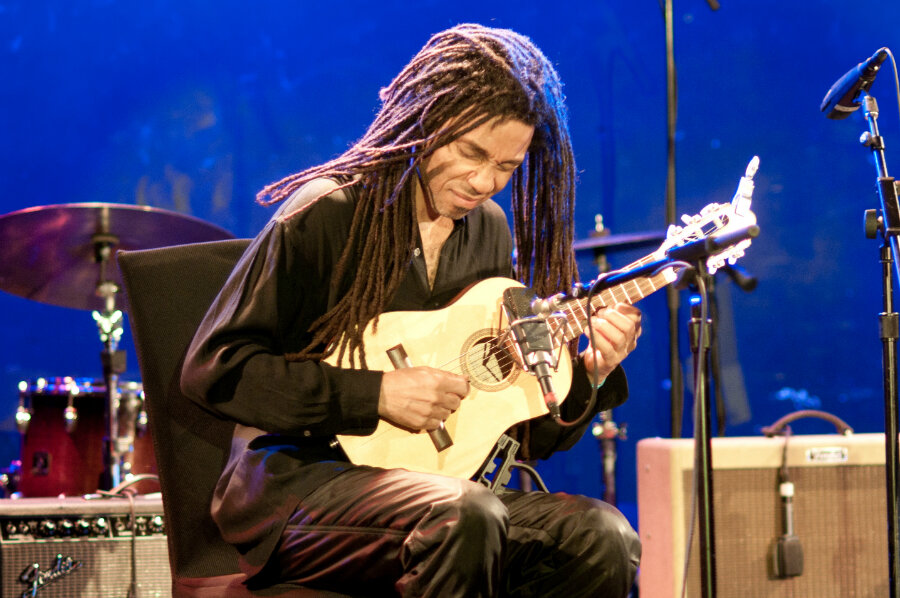

Sound and Environment: Brandon Ross Speaks

Guitarist Brandon Ross and bassist Stomu Takeishi have been playing together for over two decades, first as members of Henry Threadgill's band, then as an intimate duo, beginning in the year 2000. Honing their interplay over many years, the pair released their debut studio album in 2014, Revealing Essence, originally composed with a Chamber Music America New Jazz Works grant.

This Thursday, July 19, the duo returns to The Jazz Gallery for two sets. We caught up with Brandon by phone and email to talk about the duo's history and his own evolving relationship to sound.

The Jazz Gallery: What is it like to have such a longstanding musical partnership with someone developing into such a personal, intimate practice?

BR: I think it’s an interesting thing. I mean, longevity in this respect is something you can’t know about till you know about it—until it happens. In that way, it’s one of these really wonderful surprises. We constantly refer to that period, that band—Make A Move—when we were in it, because it was such a pivotal moment for Henry [Threadgill] in his writing, and in his ensemble selection. He went from having bands that always had at least multiple horns in it and multiple strings to a band that had a form of keyboard, with the harmonium and accordion, and then one string, and then bass—electric bass, first of all—and drum set, and himself on winds. And then it was also the beginning, during the Make A Move era, of his evolving his compositional approach into the current intervallic system that he’s been developing for the last twenty, almost twenty years now. It was a seminal period for us—Tony Caesar, Jake Lewis, Stomu and myself—being involved in that.

And so Stomu and I have that as a reference point in terms of musical dynamics, musical language. What we have been able to distill from that experience at that time, and evolve and mature in the duo relationship that we have. Although, you know, the duo relationship was already present when I heard him play and I recognized him as someone that I would like to play music with, and I happened to do that in the context of Henry’s band—cause, y’know, Henry asked me to keep my eyes out for a bass player and a drummer. So that was J.T. and Stomu, so ultimately, in a way, was a band that I had yet to realize but wound up becoming so. And I guess the longevity of the language that we share and that we developed is something that is has a lot to do with the instruments that we’re playing—Steve Klein-designed instruments. They have such a particular character of sound production and the way they interact with one another - we just want to hear them! In the writing that we do, I just want to hear the instruments [laughs].

TJG: You’ve made note of how the compositions focus on balancing the weight of the two instruments, with Stomu on acoustic bass and you on either acoustic guitar, soprano guitar, or banjo.

BR: It’s a common compositional practice: you begin with a sound of some kind. Certain instruments, certain sounds send the imagination and the creative impulse in a particular direction as a response to it. That’s an interesting thing. This last set of music that I’ve written for us, for the Chamber Music America New Jazz Works grant that I got, and I incidentally happened to be playing a lot of nylon string guitar, and most of that music came out of that—being on the nylon string guitar. Stomu and I did a concert last weekend at the Guild Hall in Easthampton where we played a couple of those pieces. I was playing the steel string guitar and I really noticed how they felt very differently from being played on the nylon, and I was like, right, these are choices and musical circumstances and situations that came about as a result of that.

TJG: This is Immortal Obsolescence?

BR: Yes, exactly. Which I have yet to record but hope to do so soon.

TJG: Graham Haynes and J.T. Lewis are also in this group, right? In what way, if at all, is it a departure from the way the first For Living Lovers record sounds like just between the two of you?

BR: Well, you know, that group—these are people who I have longstanding musical relationships with. I started a quartet when I did my first recordings for a Japanese label, which was Stomu, and J.T., and Ron Miles on cornet. Ron is out in Colorado, so it’s not as convenient to have him on gigs. And Graham is also one of the few people that play cornet and also have their own sound, and we also share a lot of musical experiences and mentoring by different musicians that we played with coming up. So that knowledge and that insight, that configuration of strings and brass is something that I’ve actually been doing since 2004, plus drums and acoustic bass with Stomu. I guess the difference is how the information is distributed in the ensemble, and the weight of that, and also how things move fluidly. You know, playing with Stomu is really pretty effortless

TJG: I think Stomu has used the word “telepathic”

BR: Yeah, it’s a lot like that. He’s able to interpret the guitarisms onto the bass in a way that really makes sense. Sometimes he’ll play things and I’ll say, wow, what was that? And he’ll say, that was the harmony you wrote. And I’ll say, let me hear that on bass. It represents another way, and it’s pretty great. I remember him telling someone once—we did a concert and there was a Q&A afterwards—and someone asked, how much of what you do is written and how much is improvised? Because it’s hard to tell. And he said, well, basically eighty percent of what I’m playing, Brandon has written, and the other twenty percent is, again, just jumping from that structure into an act of creation that is built off the integrity of the formation of the composition. It’s not just like, you’re just playing any old thing.

TJG: How was the music for this new record put together?

BR: These compositions [from Immortal Obsolescence] were also specifically written in response to a series of photographs, so they represent honest impression of a response to something visual that I found to be engaging and compelling enough.

TJG: In what way have the rest of the band interacted with them?

BR: I couldn’t say for sure—they’ve seen the images when they are projected above us. And I remember J.T. saying something like, this writing has really become more focused in this particular area. They’re short pieces, a lot of them, and they’re not necessarily about a lot of so-called improvisation, but rather statements that accomodate the interpretive abilities of the musicians to fill them out and realize them. They’re meant to accompany these images and yet stand alone as well.

TJG: Is the duo performance at the Gallery going to draw from your 2014 Sunnyside Records release, Revealing Essence?

BR: We’re playing a lot of material that hasn’t been recorded yet, actually, but that was composed at that time. But also, some of that music on that recording we haven’t performed since that recording, which we may get into it.

TJG: Ah, what hasn’t been performed?

BR: "Saturation" is a piece we haven’t performed very much. I think it’s very demanding for an audience and, you know, that is something that I do give some attention to. Okay, so, how will this be received? But with The Jazz Gallery audiences, that is not so much of an issue. But it also a piece that needs a specific kind of environment to really bring out what that’s about. You know, the music does well in situations where you can have a lot of quiet and where the space can lift up and resonate with what these acoustic instruments are doing. Spaces like that are out there, but they’re not necessarily so common in so-called jazz venues.

TJG: I’ve seen that on some of your music, you’ve employed sound designers.

BR: There’s a sound design DJ, so to speak, named Hardedge with whom I’ve been working a lot. He and Graham Haynes had a duo that they did years back that they still do occasionally, and he’s been working a lot with Wadada Leo Smith. They put out a recording called The Nile, which is really beautiful, and very demanding. And then Hardedge initiated a project called Dark Matter Halo, which I’m a part of on electric guitar, with Doug Weiselman. He brings to the sonic palette some possibilities that, and I’ve said this before in an interview, “the possibility of many different kinds of sound representations from one force.” So, rather than an instrumentalist—a harpist or cellist, for example—with extended techniques and amplification you can get to certain places. But with this sound design aspect, it’s very interesting what that can do. And our culture now is very acclimated to the experience of digital sound and sound generated that does not depend on air.

TJG: [laughs] Very true—as a millennial, I feel that we’ve assimilated everything from mechanical sound to computer sound, to post-digital sound and beyond.

BR: Exactly, and it’s an interesting thing, a beautiful thing, because it starts to incorporate the environment and the barrier of what’s music has come down to a great degree. And at least people’s ability to listen, and accept certain kinds of sound, has expanded. At the same time, I think there’s still a kind of absence of sensitivity to the power of pure acoustic sound—because that’s an amazing thing, to sit and listen to a bunch of violins or cellos, or a bunch of anything, and understanding what these things are doing in terms of a sound world and vibrationally, how they impact human consciousness and non-human consciousness in the environment, with plants and animals. So, in For Living Lovers, it’s just a situation, a place where I can really indulge in that and deal with the purity of what can be done with my hands and a box with wire on it in front of me, interacting with this other dimension of creation that mirrors it, producing a frequency range. I think it’s kind of a beautiful thing. It can be very immersive and transforming to listen to us when we’re at the peak of what we’re doing, in the moment, and flowing like that. It’s a way of revealing something, revelation about the presence of the wonder of being.

TJG: Do you amplify your instruments when you play in a live setting?

BR: No, I just put a microphone in front of it.

TJG: Is there consideration given to amplification? The electroacoustic or, perhaps, architectural qualities of the sound you’re creating.

BR: I guess you could use that word to talk about it—if you’re composing, and you’re organizing sound in some way, then yeah, there’s an architecture to it. There’s also what I like to think of as the meta-structures of music, which is something that develops in a dimensional aspect above the sound, or beyond the physical sound. I remember listening to this Morton Feldman thing a while back—something at Issue Project Room before it fully opened at its latest location, and did a Morton Feldman string quartet that was 10 hours long or something [laughs]—and it was really beautiful. You get this thing that’s erected over this time that’s real. The vibration and sound creates geometric expressions, geometric manifestations. You can see through a scientific process—these things carry information of a nature that’s not necessarily intellectual in nature, in its character, but that is vital! It communicates vitality, or the opposite of that. Something being amplified allows me for—if it’s an acoustic instrument being amplified, not even plugged in, but with a microphone in front of it—allows for it to be more encompassing and more immersive for a listener and to experience the subtlety about sound, and not just the sound that you’re hearing that’s obvious. What’s articulating sound? Silence is that which articulates sound. So maybe we’re articulating silences, really, and the sound is secondary.

TJG: In the notes for Revealing Essence, you make the note that, for one of the tracks, the banjo inflections are suggestive of Asian and African instruments. In bringing together the guitar and the banjo, you seem to be foregrounding the chordophonic nature of folk music. What originally drew you to the banjo, which has always seemed like a fundamentally American folk instrument, and is there something inherent to its sound that makes it fit for representing this “pan-ethnic” quality?

BR: As I mentioned when we spoke, sound is everything... As a point of departure.

And in fact I do feel that there is a primacy connected with chordophones, from multiple levels of consideration. There’s a common acceptance of the voice as the primary, or perhaps, primordial expression of communicative creative sound in humans. But even there, with the voice, we are talking about vocal cords—the rate of vibration of “stringed membranes.” Since I’m not a musicologist, I will defer to a more studied analysis, but then perhaps percussive sound. And then a string. A sound generated impulsively, with many practical and functional applications.

In particular, in what we call Jazz, the idea that strings occupy a subordinate position to horns, and keyboards (with double bass as the standard exception), belies the succession from early string bands; blues and the banjar—precursor to the modern banjo—reconfigured in the new world, by enslaved Africans. If we look to the East, we have a rich and ancient tradition of countless evolved expressions of chordophonic musics.

The banjo, is a tunable drum, with strings stretched across it. Depending on the setup, it can sound extremely modern, or very close to its ancient ancestral roots. For me, we are discussing Folk Musics at that point—we are considering essential vibration, Pythagoras, Egyptian sound science, spirituality, high-technologies, both outer and INNER...

The banjo decays quickly, and yet is capable of surprisingly high levels of volume without electronic amplification. Modern instruments contain a tone ring which serves to amplify the sound, but banjos without them, are these intimate, Pan-cultural communication devices that inspire a form that, strings exemplify.

All of those observations drew me to the banjo, and the textural opportunities of modern or contemporary music played on something very old—can that, does that actually work? Which is transformed most significantly, the experience of the music or the instrument’s capabilities?

It’s what I like about the soprano guitar also. It can actually sound like a concert harp, a Koto, a ukulele, a mandolin, and a guitar, depending on the context and the music being played in it.

Stomu and I have pursued the nuance of those intersections of timbre and content and form, and we exploit it in a way that defines what For Living Lovers means.

I mean, whatever speaks to and from one’s heart, is typically what drives and advances the act of creating. That thing, the essence that continually reaches to fulfill itself, and convey itself, is in my view, the only thing happening on the planet! Persisting in revealing itself through all, that is.

Brandon Ross, guitar, and Stomu Takeishi, bass, play The Jazz Gallery on Thursday, July 19, 2018. Sets are at 7:30 and 9:30 P.M. $20 general admission ($10 for members), $30 reserved cabaret seating ($20 for members) for each set. Purchase tickets here.