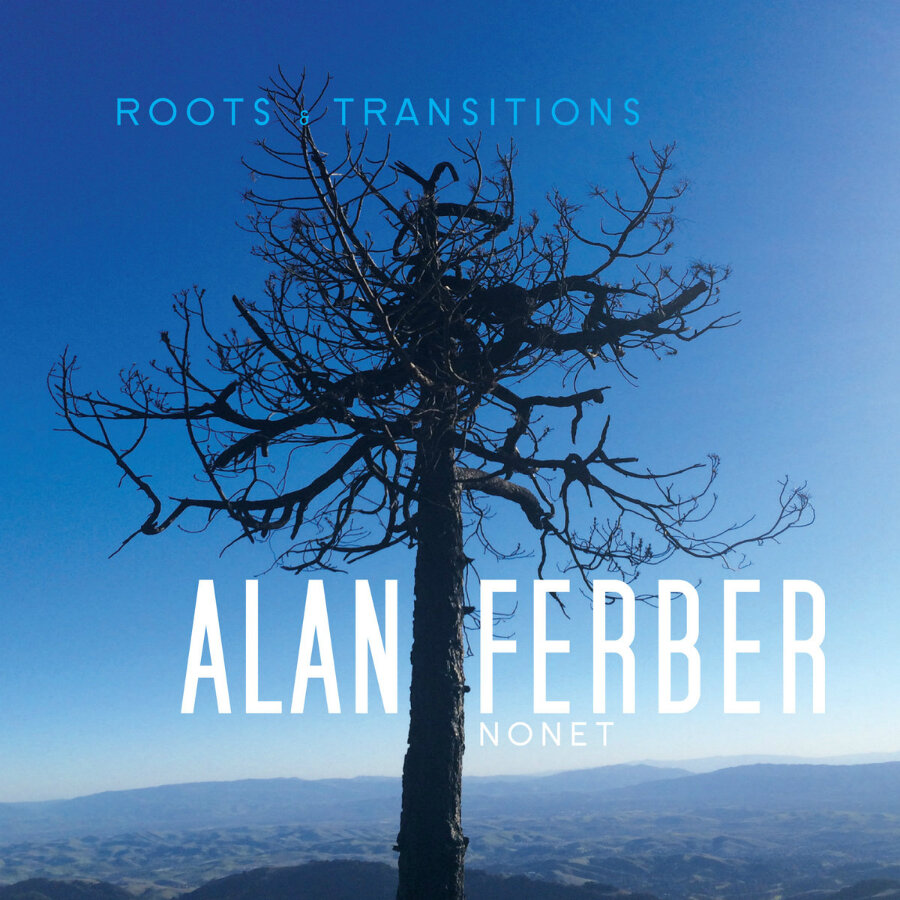

Roots and Transitions: Alan Ferber Speaks

Alan Ferber's previous album March Sublime (Sunnyside) marked the trombonist and composer's first major foray into writing for big band and netted him his first Grammy nomination. For his latest album, Roots & Transitions (Sunnyside), Ferber has stripped down his palette, returning to his long-time nine-piece band. The album features a suite of new music commissioned by Chamber Music America and inspired by Ferber's experience as a new father, watching his infant son grow and change.The Jazz Gallery is thrilled to welcome Ferber back to our stage to celebrate the release of this beautiful and deeply-personal music. Jazz Speaks caught with Ferber by phone to talk more about his compositional process for the suite and balancing his work as a performer, composer, and father.The Jazz Gallery: You’ve got two shows coming up at The Gallery–a two-night album release for Roots & Transitions. The liner notes for the album are written so beautifully and sensitively. Was that all your writing?

Alan Ferber's previous album March Sublime (Sunnyside) marked the trombonist and composer's first major foray into writing for big band and netted him his first Grammy nomination. For his latest album, Roots & Transitions (Sunnyside), Ferber has stripped down his palette, returning to his long-time nine-piece band. The album features a suite of new music commissioned by Chamber Music America and inspired by Ferber's experience as a new father, watching his infant son grow and change.The Jazz Gallery is thrilled to welcome Ferber back to our stage to celebrate the release of this beautiful and deeply-personal music. Jazz Speaks caught with Ferber by phone to talk more about his compositional process for the suite and balancing his work as a performer, composer, and father.The Jazz Gallery: You’ve got two shows coming up at The Gallery–a two-night album release for Roots & Transitions. The liner notes for the album are written so beautifully and sensitively. Was that all your writing?

Alan Ferber: Yeah, I wrote most of it, and then sent it to Sunnyside to edit it. It’s a project that I’m pretty intimately connected with in a big way, on a number of levels.

TJG: You described this idea of subjecting these small musical cells to different translations and transformations in a way that parallels your own personal development during this recent period. Could you talk a little more about that?

AF: I guess to put it into context, this piece was the result of a grant that I received from Chamber Music America’s New Jazz Works commission. When I received the grant, my wife was pregnant, so I sort of knew what my life circumstances were going to be. I knew, and I also had no idea what that was going to be like. When I received the grant, with the reality of our son being born, during that first year of his life, I was starting to write the piece and, in a way, had very little time to do it, because of my family responsibilities. I tried to think about how life starts. In particular, having a child, you see how just a little seed can develop and get more complex. When he enters the world, you see it play out in front of you. And this was so inspiring to me, from a musical perspective.Out of necessity, I didn’t have the time to focus on trombone and composition, which used to be two separate things. I started to practice compositionally on the trombone. So I was coming up with little motives and seed ideas on an instrument that severely limits you. You can’t play a chord on the trombone. You can’t have the immediate gratification of a chord voicing, which is advantageous, yet challenging. I realized that I had to come up with something, even if it was a three- or four-note idea that was compelling. Once I came up with it, I allowed the idea to gestate over a long the course of time. I would improvise with it, extend it, manipulate it, and approach it with different techniques. And depending on how I was feeling, if I didn’t get any sleep because my son was up all night, if I was anxious or edgy for example, the ideas I had would be a real reflection of that.

TJG: Could you give an example?

AF: One night, we were out and he was with a babysitter. He was in this really rambunctious stage. We came back, and he had just fallen onto a toy clock, and it was just a mess, man. He was crying his eyes out, and there was blood, and it felt really traumatic. Like, Oh my god, what do we do, should we go to the emergency room? Should we just clean it up? And this and that, and so on. It was the first time something like that had happened to us. But everything was cool in the end. And the next morning, I started to write, and was feeling this angst, which translated into angular ideas and intervals. And there’s a tune called “Clocks” on the album, which is angular, edgy, and not terribly comfortable-sounding.

TJG: On “Clocks,” Jon Gordon and Nate Radley’s solos are absolutely huge.

AF: Yeah. Their solos contribute compositionally to the piece. And I realized, as I was composing this tune, the ‘seed’ idea, a perfect forth surrounded chromatically that serves as the first part of the melody, I realized that I had sort of almost stolen it subconsciously from this free improvisation from one of Jon Gordon’s records. It had this kind of contemporary improvisation between him and Bill Charlap. It’s this strange and beautiful intervallic seed idea, and it became the main idea for “Clocks,” and so it felt appropriate to have Jon solo over it, considering how he informed it.

TJG: Did he know where you’d taken the idea from?

AF: He didn’t, until I told him eventually. He was like “Oh. Really?” And I actually saw Bill Charlap the other night and told him too, and he was like “Woah, crazy!” [Laughs] It was an improvised track from one of their records, where they grabbed that motif and played around with it for a while. It got into my subconscious and informed the piece. The fact that it was also informed by this traumatic life experience says something to how certain musical ideas can surface or resurface depending on how you’re feeling.

TJG: When you embarked on this project, you must’ve anticipated some of the challenges associated with your circumstances. What were some of the most unexpected elements?

AF: To be honest, the switch to trombone was not planned, which caught me off guard. That was a direct result of a necessity. I had no intention of composing this thing on trombone. The fact that that happened was new and surprising. The other thing that caught me off guard was that as a jazz musician and composer, I had always sort of just written one tune at a time, maybe months between tunes, until I said “Oh, I’ve got eight tunes, I guess I should do a record now.” This concept of writing a piece stemmed from having this limited amount of time to write a lot of music, which I had never done. I didn’t really think about it until midway, but I realized that these motivic seed ideas were beginning to travel across to other tunes. I would be writing more than one thing at once, and one thing would generate an idea for another, and things were happening simultaneously. Different but related ideas were coming together just by the fact that I had this short window of time to write. And I did put a concentrated three or four months into writing the piece. It turned into a piece connected by motives, and I hadn’t really written that way before. I also began thinking about myself as an improviser, and wondering how I could incorporate that into my compositional process. I’d never been a chord-scale type of player. It’s been more like a ‘playing and embellishing melodies’ approach to improvisation. This way of using motifs creates a longer and more exciting story, with a newfound depth and dimension. You can hear more as you listen to and revisit the music.

TJG: So, themes talking between movements, ideas developing over time; as you were constructing and composing, how did your process look? Did you have lots of recordings, were you doing it all on paper, were you using a computer? What was your approach?

AF: I had this initial sketch that had most of the information that permeates the piece. That sketch is the eighth movement. I had done this sketch beforehand, and had this bassline figure. I wrote a one-page sketch, and ended up always having it next to me, because when I started running out of ideas, I’d mine that sketch for more material. The bassline is a rhythmic minor-seventh figure. I’d take that and try inverting it, and used that subsequent diad at the beginning of “Clocks.” That’s an example of taking a linear melody from the trombone and organizing those notes in multiple ways. There are a lot of melodic ideas from the sketch that permeate the other movements. They’re the primary motifs that are present throughout the movements.The other thing is that I worked almost entirely with pencil and paper. I really wanted to stay in my imagination for as long as possible. I wanted to stay away from the computer, and even the piano, because I knew that those things might start to make musical decisions for me. I didn’t want to orchestrate things too early on. I wanted to keep things linear and contrapuntal. I had a lot of pencil sketches that I was working with as well. When I exhausted what I could do on the horn, I moved to the piano. I’m a composer-pianist, not a true pianist, so the piano was still limiting as well. So I’d move an idea to the piano, and find harmonic ideas that worked around the linear ideas, and would finally move to the computer for final development at the last minute.

TJG: As a trombone player, would you say to yourself, “I should be able to do everything on trombone, I don’t want to use the piano or computer; all I need is my imagination?” Did you ever feel concerned if you felt an urge to move to the piano?

AF: Well, I’d come up with linear ideas on the trombone, but as I was playing them over and over, I’d develop a mood in my head and my imagination that I wanted. I’d play it over and over, move it around, transpose it. The sound of the trombone is so songful and expressive. Every note sounds so different. Ellington would have these crazy orchestrations of high muted trombones with low clarinets, for instance, because he really thought about these things. This way of thinking makes a lot of sense, to take traditional instruments and flip them out of their roles. As a trombone player, when I’m composing on the horn and working in the upper register, there’s a singing quality where I begin to abstractly hear things below that. Voicings, maybe, or just orchestrations. If I stay away from a harmonic instrument for long enough, it can really become a full orchestral sound in my head. It’s almost like I have this whole band in the room, if I have long enough to meditate on the idea. But it’s just me.If I allow that process to happen, all I have to do is go to the piano and find the sounds. It’s so much easier to take that approach than if you’re going to the piano and are just like “Uhhhh, let’s see, I’ll plunk this random thing out, and eh, this isn’t really cool, and...” It’s much harder and more frustrating that way. You don’t know what you want and what mood you’re trying to strike. Anyway, I really wanted to just massage an idea on the horn until I had this full conception of what I wanted before moving to something with more options, like the piano.

TJG: I’m thinking of the horn backgrounds at the end of your solo on “Quiet Confidence.” They’re so low, rich, smooth, and powerful. How did you ultimately decide on the nonet as your configuration.

AF: Well, this is my fifth album with the nonet. It was a band that I knew. I had been working on big band for three intense years, and wanted to thin it out, to take a break from that intensity. I wanted to do more chamber music again. I missed the one-player-per-part idea. As a sideman, I missed just playing a melody by myself in an ensemble context, rather than always being unison with someone else. Playing with the nonet feels almost naked compared to what I was doing before.Those backgrounds on “Quite Confidence” actually are the melody of the song, voiced in a couple of instruments as a midground texture. I like to use melodies and melodic backgrounds that I can improvise with, contrapuntally. That melody is just a lot of long tones, very slow paced, so it’s conducive to that approach. And that concept ties the piece together.

TJG: Once you came to the end of the compositional process–writing and editing, then rehearsing, releasing, publishing, and now touring–were there any loose ends that you felt like you didn’t really have time to touch on in the piece? Did you have goals that you didn’t have time to reach, or ideas you’d like to revisit for a future project?

AF: That’s hard to answer, in a way. One thing that always frustrates me is that it’s hard to just play the piece enough. I tend to make a lot of large ensemble recordings. After it’s recorded and distributed, it’s hard to make opportunities to play it. Touring with a nonet and a big band is really difficult—there’s a lot stacked against you. That always creates some frustration for me. This love for large ensemble music and ensemble-based music is not like a trio, a far more viable touring unit. Financially, it’s rare that I can make the nonet happen. I put a lot of work into my records, and I did a lot of rewrites of this project, but there are some things in the music that as an ensemble, we could take the music to new and different places if we had the time to play it. But with months between performances, it feels hard to gain momentum on the music that way.So the next step is trying to figure out how to just play it more. One thing I’ve though about is traveling with certain people that can help cohere things. So I’d travel with my three or four core people, then get locals from wherever we go. That might make it possible to make some strong statements in a short amount of time. I’m here in Kansas City now, and these guys haven’t played the music before, and it’s sounding great. But you always wonder what could happen with just a few more dates. So that’s the next frontier for me. Making the music has been relatively easy to do, but creating opportunities for the next frontier is the challenge.

TJG: Well, we’ll be looking out for what you do next. We can’t wait to see what happens.

AF: Thank you! And the upcoming Jazz Gallery shows are so meaningful. The Gallery has been an incubator and has provided space for me over the years to try all these ideas and experiments. The first ensemble that Rio allowed me to try was my nonet, years ago, in a project that I did with strings. To return with this ensemble is cool. And it’s nice to have a relationship with a place whose mission is to provide a space for people to try new things out. Rio is such an influential figure on the New York scene for that reason. She allows people these opportunities to try new things. You need to have that feedback of what it’s like to play new music for a live audience in order to move forward.

The Alan Ferber Nonet celebrates the release of its album Roots and Transitions (Sunnyside) this Friday, May 13th, and Saturday, May 14th, 2016. The group features Mr. Ferber on trombone and compositions, Michael Rodriguez on trumpet, Jon Gordon on alto saxophone, John Ellis on tenor saxophone, Charles Pillow on bass clarinet, Nate Radley on guitar, Bryn Roberts on piano, Matt Pavolka on bass, and Mark Ferber on drums. Sets are at 7:30 and 9:30 P.M. each night. $22 general admission ($12 for members) for each set. Purchase tickets here.